Study Reveals Stark Inequalities in TVET Training Facilities Across Ashanti Region

A new study commissioned by UNICEF Ghana in collaboration with the government of Ghana has exposed sharp disparities in the quality of infrastructure and workshop facilities in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions across the Ashanti Region.

While some schools boast modern, well-equipped workshops, others are struggling to provide even the most basic tools, undermining the very essence of vocational training.

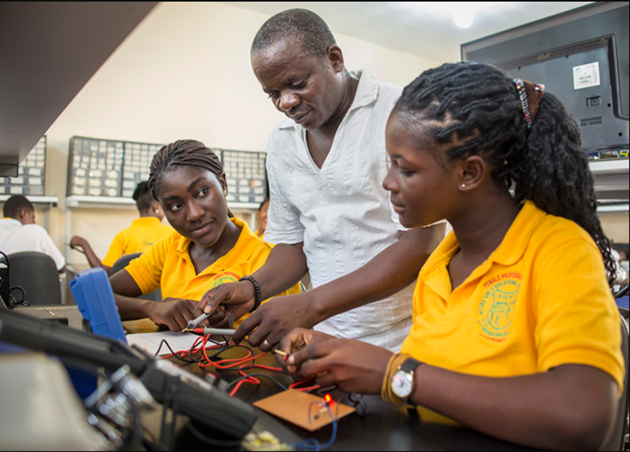

The findings, which assessed the state of workshops and training equipment, revealed that although most institutions claim to have facilities for their trade areas, the quality varies widely. Institutions with better infrastructure are typically accredited by the Commission for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (CTVET) for Competency-Based Training (CBT) and often benefit from donor-funded projects like the TVET Voucher Project.

But for many students, the reality of “hands-on learning” is far from ideal. At Offinso Technical Institute, Electrical Engineering students expressed frustration over having to improvise practical sessions in classrooms due to the lack of a functional workshop.

“We don’t have a workshop for practical; we use our classrooms instead. The school has very few tools, so we are required to buy our own,” one trainee lamented.

The situation is not much better at Abosamso Technical Institute, where makeshift classrooms double as workshops. Students reported that the added burden of buying their own materials places significant financial strain on families, raising questions about the accessibility of TVET education for disadvantaged learners.

Engineering-related trades appear to be the hardest hit. Trainees in Electrical Engineering, Building Construction Technology, Wood Construction Technology, Catering and Hospitality Management, Architectural Draughtsmanship, Automobile Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering reported widespread dissatisfaction with their workshop conditions.

Even in schools with modern facilities, access is not guaranteed. At Kumasi Technical Institute, students said they are sometimes denied use of well-equipped workshops due to management fears of equipment theft.

“Yes, we have workshops with modern equipment, but the school does not allow us to use them because they think we will steal the equipment,” a female Auto Mechanics trainee revealed.

In stark contrast, institutions offering Fashion Design Technology, Computer Hardware and Software, Welding and Fabrication, Cosmetology, and Automotive Engineering reported much higher satisfaction levels. About 95% of schools offering Fashion Design Technology confirmed they had functional workshops.

At Bethel School of Fashion and Design, one trainee said the availability of modern facilities was a major factor in her decision to enrol.

“Our school has a workshop equipped with modern sewing machines, and we are allowed to use them. In fact, I was motivated to enrol because of these modern machines, and I have not regretted choosing this school,” she said.

Analysts note that private Technical Institutes (TIs) are often able to maintain higher standards because they specialise in fewer programmes, allowing them to focus resources on equipping their workshops to accreditation levels.

The study concludes that these disparities threaten the core mission of TVET—preparing students with practical, industry-relevant skills. Without urgent investment in infrastructure and training materials, many young people risk leaving school ill-prepared for the demands of the labour market, despite choosing TVET as a pathway to employment.