World Bank Report Links Environmental Management to Jobs, Warns of Risks for Developing Economies like Ghana

A new World Bank Group report, “Reboot Development: The Economics of a Livable Planet,” has revealed how natural resources continue to shape employment and productivity across developing economies. The report highlights both opportunities and risks, stressing that if poorly managed, natural wealth can undermine long-term job creation and growth.

Natural Endowments as Engines of Work

Globally, almost one in three workers, about 3.2 billion people, earn their livelihoods directly from food systems and primary production. For many developing countries, fertile land, fisheries, and forests remain the backbone of employment. These natural assets provide food security and anchor entire value chains in agriculture, aquaculture, and tourism.

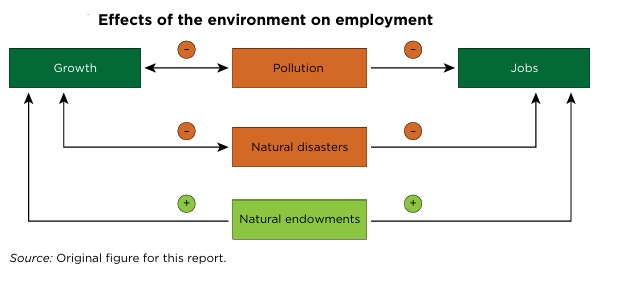

The report makes clear, however, that natural resources are not limitless. Pollution, land degradation, and unsustainable exploitation reduce productivity and erode human health. While pollution-intensive industries may create jobs today, the toxic legacies they leave behind diminish the future potential of workers and economies.

The Role of Fisheries and Agriculture

The fishing industry is a strong example of how environmental pressures directly impact livelihoods. Globally, about 61.8 million people were employed in fisheries in 2022, a decline from 62.8 million in 2020. Declining catches, changing methods, and climate pressures are reshaping the sector. The World Bank notes that investment in cold storage, processing, and sustainable aquaculture can help fishing communities move beyond subsistence and create better-paying jobs.

Agriculture also remains a powerful driver of employment but carries its own set of challenges. The World Bank revisits Nobel laureate Sir Arthur Lewis’ theory on structural transformation, which explains that long-term growth happens when labor shifts from low-productivity farming into higher productivity industry and services. However, this transition is neither automatic nor guaranteed. In some places, rising farm productivity attracts more workers into agriculture, while in others it sparks urban migration and diversification.

The Ghanaian Experience

These global dynamics are clearly visible in Ghana. Agriculture still employs over 30 percent of the workforce, while millions depend on fishing, forestry, and related natural resource sectors. Yet, these very foundations of employment are under growing pressure.

Illegal mining has polluted major rivers such as the Pra and Ankobra, threatening water security and reducing the productivity of both farming and fishing. Ghana’s forests are depleting at an alarming rate, weakening eco-tourism potential and putting rural jobs at risk. Coastal and inland fishing communities face dwindling catches, forcing many households into economic uncertainty.

Despite Ghana’s gradual urbanization, the structural transformation the World Bank describes has been uneven. Many new urban jobs have appeared in informal trade and low-value services rather than in industry. In cocoa-growing regions, productivity gains often pull more labor into farming rather than freeing workers for other economic opportunities.

Balancing Short-Term Gains with Long-Term Security

The report argues that countries like Ghana must strike a careful balance between short-term job creation in natural resource sectors and the long-term sustainability of those resources. Investments in nature-based enterprises, sustainable farming practices, and rural value chains are presented as a pathway to achieve what the World Bank calls a “double dividend”: creating employment today while safeguarding the environment for tomorrow.

For Ghana, the lesson is simple but urgent. Protecting rivers, forests, and fisheries is not just about preserving ecosystems. It is about securing jobs, boosting productivity, and ensuring that natural resources remain a foundation for growth well into the future.